Bloomburg Law 11/10/2020 by Ian Kullgren

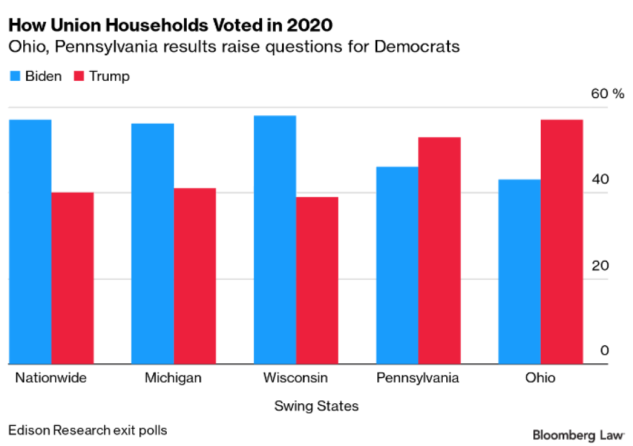

Union votes helped President-elect Joe Biden win the crucial swing states of Michigan and Wisconsin, but a majority of union households backed President Donald Trump in Ohio and Pennsylvania—raising questions about how Biden can use policy to shore up Democrats’ “Blue Wall.”

Biden won 57% of union households nationwide compared with 40% for Trump, according to Edison Research, which produces exit polling for major news organizations. That was double Hillary Clinton’s eight-point edge with union households in 2016.

In the 2020 election, where polling writ large has been widely criticized for inaccuracies—and Trump is still contesting the outcome—any conclusions that can be drawn from exit polling data are debatable at best.

Yet Edison’s exit polls, which included phone interviews with mail-in voters as well as in-person surveys at polling sites, showed Trump expanded on his 2016 tally among voters who identified themselves as members of a union household in Ohio and in all-important Pennsylvania. That would have been a troubling result for any Democrat, but it was especially painful for Biden, a candidate whose blue-collar roots are central to his brand and who put union voters and middle-class jobs at the heart of his economic message.

“This is not just a branding difference,” Seth Harris, a former acting labor secretary during the Obama administration, said. “This is someone who has unions and union families front and center in his policymaking, and he communicated that unabashedly.”

The mixed results reinforce Trump’s uncommon appeal among some union workers, and suggest that his protectionist trade policies and conservative stances on social issues may continue to sway union members and their allies.

Biden will have to give careful thought to policy decisions that could influence union support for Democrats in Rust Belt states during the 2022 and 2024 elections. Examples include potential moves to address climate change, income inequality, immigration, and use of force in policing, and whether to aggressively promote a sweeping, union-backed labor bill that passed the House earlier this year.

“We’re in a time in which a significant number of labor households are no longer single-issue voters for labor,” Jay Nixon, the former Democratic governor of Missouri, said. “But, it’s an important constituency.”

Labor leaders are skeptical of the results in Ohio and Pennsylvania, given the high percentage of mail-in votes in this election. They insist that exit polls undercounted union support for Biden, while former elected officials and local Democratic Party leaders said the numbers tracked with declining enthusiasm for Democrats among union workers and a steady drift toward Republicans.

Numbers Questioned

Biden plowed over Trump in Wisconsin and Michigan, winning 58% and 56% of union households in exit polls, respectively. The gains were enough to reverse Clinton’s losses among union households but still fell below former President Barack Obama’s union totals.

In Pennsylvania, Trump won 53% of union households, besting John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012. Biden won just 46%, according to Edison Research.

Internal AFL-CIO polls showed Biden ahead with more than 55% support, Pennsylvania AFL-CIO President Rick Bloomingdale said.

In Ohio, Trump won 57% of union households, while Biden picked up just 43%.

“It’s a very big gap and, frankly, it’s hard to fully grasp,” Steve Rosenthal, a former political director for the AFL-CIO, said. He led a union-backed effort to ensure former members turned out on Election Day.

Exit polls alone may not capture the full union vote, union strategists said, citing ex-members who still align with Democrats and those who didn’t report their membership status on exit polls.

Still, the AFL-CIO, the country’s largest labor federation, representing 12.5 million workers, was quick to claim victory. It said its members favored Biden by 21 points in an internal post-election survey.

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka told reporters late last week that Biden’s Rust Belt firewall was “union made.” The new administration would move quickly next year, he said, to add union-friendly members to the National Labor Relations Board, where the current Republican majority’s pro-management policies have infuriated organized labor.

“We will get people who are pro-workers,” Trumka said. “The law of the land does not say we will tolerate collective bargaining; the law of the land says we will encourage collective bargaining.”

Biden, who has spent decades cultivating union workers in Rust Belt states and kicked off his campaign at an International Association of Fire Fighters hall in Pittsburgh, is widely expected to shift federal agencies’ focus away from Trump’s business-friendly philosophy.

‘Union Man’

“The influence is there because Mr. Biden is a union man,” said Michael Lotito, a management-side attorney at Littler Mendelson who focuses on federal workplace policy. “He doesn’t have to be sold on these concepts.”

But Biden’s mixed bag of union support in key Rust Belt states could influence how far in workers’ direction he chooses to go. A leading question is whether Biden will spend political capital to promote passage of unions’ biggest legislative desire: the PRO Act, a wish-list of pro-union measures to reverse declining membership.

It also could hold sway over how Biden will approach the NLRB, one of the few places where his administration could make significant changes to labor law without legislative approval.

The possibility of Republicans retaining control of the Senate could force Democrats to abandon the idea of sweeping labor reforms, for now. That would require Biden to focus on regulatory moves and smaller changes that could be made solely by the NLRB, the Labor Department, and other agencies.

Biden’s poor showing in Ohio raises doubts about unions’ strategy for turning out members, especially because the pandemic largely prevented them from conducting in-person canvassing. But it also speaks to Trump’s continued appeal in some union-heavy areas.

“We didn’t do a good job in Ohio, that’s the truth,” said Charlie Bush, chair of the Clark County Democrats and a retired United Auto Workers member. “I really don’t know. We did everything we were supposed to do.”

Democrats had criticized Trump over the closing of a 6.2-million-square-foot General Motors assembly plant in Lordstown, Ohio, last year, using the layoffs to drive home their argument that Trump’s economic and trade policies have failed blue-collar workers.

In the end, Trump routed Biden by 10 points among union households in Trumbull County, which includes Lordstown, on his way to taking the state by eight points—Democrats’ second consecutive loss in Ohio in a presidential election.

Trade Factor

One likely factor is that the Trump administration renegotiated the North American free-trade pact to include labor protections unions had long sought. Trump attacked Biden repeatedly over Biden’s support for the North American Free Trade Agreement, which many union workers blamed for encouraging companies to shift manufacturing jobs to Mexico, where labor costs are far lower.

And there are less-tangible aspects of Trump’s appeal among union households—an enduring frustration for Democratic politicos.

“I don’t think he gives a damn about a working person, but somehow he’s been able to convince them—some of them—that he’s on their side and he’s fighting for them,” Ted Strickland, the former Democratic governor of Ohio, said. “You have to hand it to Trump, he is pretty good at that kind of marketing.”

Tim Burga, president of the Ohio AFL-CIO, disputed the accuracy of the exit polls, saying his own internal poll at the end of October showed members favoring Biden by 17 points.

“I knew these conversations would be coming. That’s why I did my own polling,” Burga said.

The Pennsylvania numbers suggest Trump’s attacks on Biden over hydraulic fracturing may have worked. Trump repeatedly alleged that Biden would eliminate union jobs, when in fact Biden had said he would only ban new fracking projects on federal land but not on private or state land, where the majority of fracking takes place.

But Biden’s message on fracking likely failed to resonate with some rank-and-file union members, who saw it as a metaphor for a broader war that a Democratic administration could wage on the coal and gas industries, Bloomingdale said.

“They’ve bought into ‘Trump’s going to bring back coal,’ even though he hasn’t,” Bloomingdale said. “We probably lost some of those members, certainly.”

—With assistance from Jim Rowley

To contact the reporter on this story: Ian Kullgren in Washington at ikullgren@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John Lauinger at jlauinger@bloomberglaw.com; Andrew Harris at aharris@bloomberglaw.com